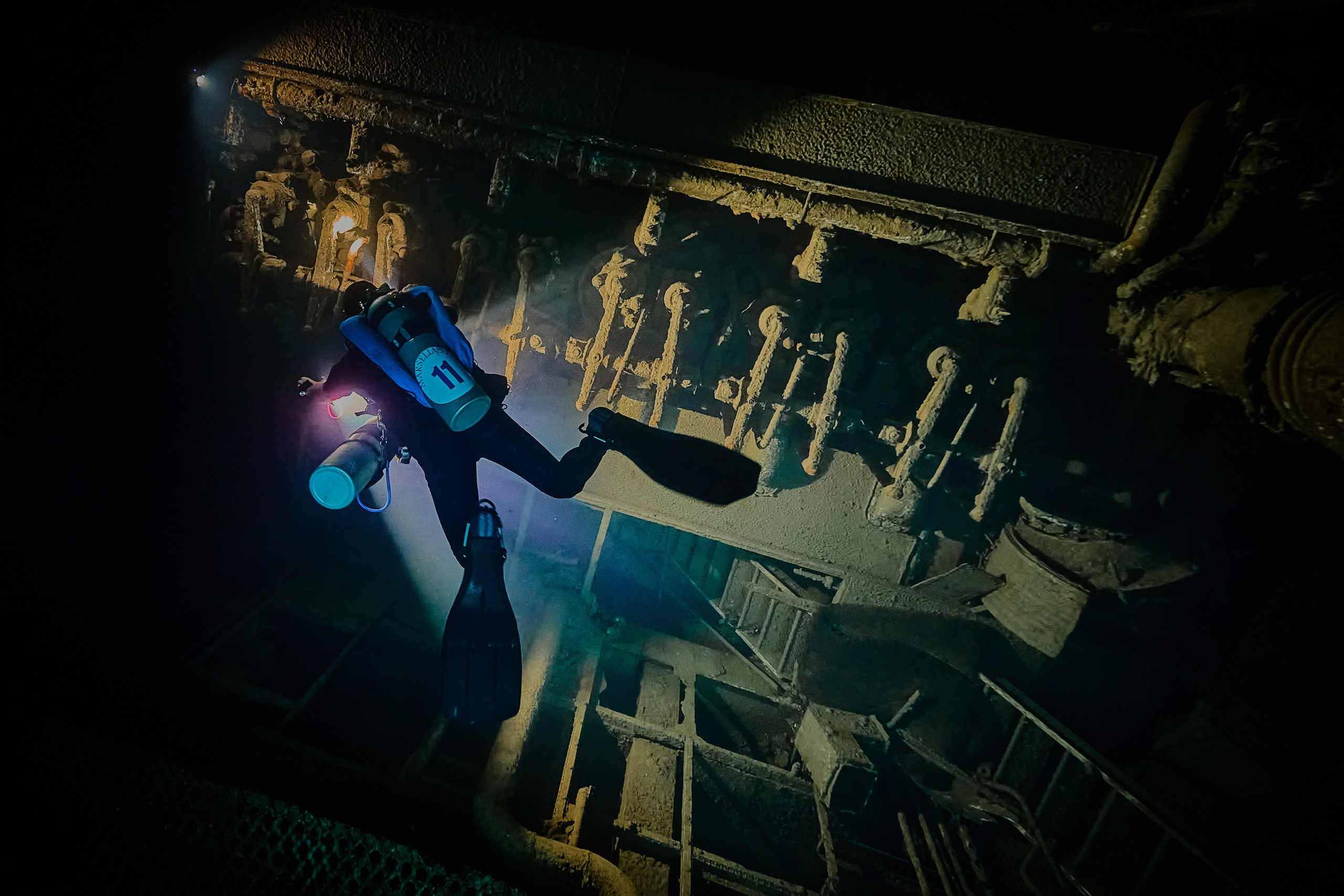

SS Thistlegorm

SS Thistlegorm was a British cargo steamship that was built in Sunderland, North East England in 1940 and sunk by German bomber aircraft in the Red Sea in 1941. Her wreck near Ras Muhammad is now a well-known diving site.

J.L. Thompson and Sons built Thistlegorm in Sunderland, County Durham, as yard number 599. She was launched on 9 April 1940 and completed on 24 June. Her registered length was 415.1 ft (126.5 m), her beam was 58.2 ft (17.7 m) and her depth was 24.8 ft (7.6 m). Her tonnages were 4,898 GRT and 2,750 NRT. The North Eastern Marine Engineering built her engine, which was a three-cylinder triple-expansion engine rated at 365 NHP or 1,850 IHP.

Thistlegorm was built for Albyn Line, who registered her at Sunderland. Her UK official number was 163052 and her wireless telegraphy call sign was GLWQ. The Ministry of War Transport partly funded Thistlegorm. She was a defensively equipped merchant ship (DEMS) with a 4.7 in (120 mm) mounted on her stern and a heavy-calibre machine gun for anti-aircraft cover. The ship completed three successful voyages in her career. The first was to the US to collect steel rails and aircraft parts, the second to Argentina for grain, and the third to the West Indies for rum. Prior to her fourth and final voyage, she had undergone repairs in Glasgow.

She left Glasgow on her final voyage on 2 June 1941, destined for Alexandria, Egypt. The ship’s cargo included: Bedford trucks, Universal Carrier armoured vehicles, Norton 16H and BSA motorcycles, Bren guns, cases of ammunition, and 0.303 rifles as well as radio equipment, Wellington boots, aircraft parts, railway wagons and two LMS Stanier Class 8 °F steam locomotives. These steam locomotives and their associated coal and water tenders were carried as deck cargo intended for Egyptian National Railways. The rest of the cargo was for the Allied forces in Egypt. At the time Thistlegorm sailed from Glasgow in June, this was the Western Desert Force, which in September 1941 became part of the newly formed Eighth Army. The crew of the ship, under Captain William Ellis, were supplemented by nine naval personnel to man the machine gun and the anti-aircraft gun. Due to German and Italian naval and air force activity in the Mediterranean, Thistlegorm sailed as part of a convoy via Cape Town, South Africa, where she bunkered, before heading north up the East coast of Africa and into the Red Sea. On leaving Cape Town, the light cruiser HMS Carlisle joined the convoy.

Due to a collision in the Suez Canal, the convoy could not transit through the canal to reach the port of Alexandria and instead moored at Safe Anchorage F, in September 1941 where she remained at anchor until her sinking on 6 October 1941. HMS Carlisle moored in the same anchorage. There was a large build-up of Allied troops in Egypt during September 1941 and German intelligence (Abwehr) suspected that there was a troop carrier in the area bringing in additional troops. Two Heinkel He 111 aircraft of II Staffeln, Kampfgeschwader 26, Luftwaffe, were dispatched from Crete to find and destroy the troop carrier. This search failed but one of the bombers discovered the ships moored in Safe Anchorage F. Targeting the largest ship, they dropped two 2.5 tonne high explosive bombs on Thistlegorm, both of which struck hold 4 near the stern of the ship at 0130 on 6 October. The bomb and the explosion of some of the ammunition stored in hold 4 led to the sinking of Thistlegorm with the loss of four sailors and five DEMS gunners. The survivors were picked up by HMS Carlisle. Captain Ellis was awarded the OBE for his actions following the explosion and a crewman, Angus McLeay, was awarded the George Medal and the Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery at Sea for saving another crew member. Most of the cargo remained within the ship, the major exception being the steam locomotives from the deck cargo which were blown off to either side of the wreck.

In the early 1950s, Jacques Cousteau discovered her by using information from local fishermen. He raised several items from the wreck, including a motorcycle, the captain’s safe, and the ship’s bell. The February 1956 edition of National Geographic clearly shows the ship’s bell in place and Cousteau’s divers in the ship’s lantern room. Cousteau documented diving on the wreck in part of his book The Living Sea.